Italian Pizza Flour: What Makes It So Special, and Is It Really ‘Better’?

Italian flours have a unique reputation for being ideal for making pizza dough and other baked goods. But what makes them so special, and are they truly essential for pizza-making (or any other baking)? This article aims to clarify these questions and offer a different perspective on Italian flour

First of all, before we dive into the topic of Italian flour, take a deep breath. What you’re about to read might challenge some commonly held beliefs and dogmas surrounding Italian flours, and it might initially seem controversial – and that’s perfectly fine.

PizzaBlab aims to present information in an unfiltered, accessible manner, and this article is no exception. Feel free to interpret and utilize the information as you see fit, but it is something that I believe every pizza lover and baker should be aware of.

To fully understand this article, I recommend first reading the following articles:

– A Guide to Understanding Flour – Types, Role in Baking, Characteristics, and Essential Knowledge (sections ‘Classification and Types of Wheat’ & ‘The Main Characteristics of Flour – Protein Content’)

– The Ultimate Guide to Pizza Flour – How to Choose the Ideal Flour for Pizza (section ‘Properties of a Quality (Pizza) Flour’)-

The Characteristics of Italian Wheat and the Composition of Italian Flour

Italian Wheat

Let’s start with the basics – the Italian wheat.

The bread wheat grown in Italy (not to be confused with durum wheat), is predominantly low in protein. Consequently, flour made exclusively from Italian wheat produces a weak dough that is unsuitable for making baked goods that require a strong gluten network, such as pizza and large-volume bread; On the other hand, Italian wheat, with its low protein content and weak gluten, is perfect for making pastries that require a soft texture, such as cakes, cookies, and danishes.

To put it simply – the local Italian (bread) wheat is far from ideal for most baking applications.

In the past (and still today), Italians have used various methods and techniques to bake bread using their locally grown weak wheat (and they had no other option, as it was the only type of wheat accessible to them before imports became feasible), adjusting their work processes to match the qualities of their wheat and flour. Some of the techniques they used include:

- Creating baked goods and breads that can be made using their local wheat, such as focaccias, ciabattas, and other flatbreads.

- Incorporating high-protein durum flour into their baked goods, like Sicilian bread and other durum-based breads.

- Utilizing sourdough or a biga preferment to acidify the dough. This process strengthens the gluten and results in a stronger dough (acidity strengthens gluten bonds).

The above techniques have proven to be effective (and still are), but they are now less relevant to the majority of home bakers, both in Italy and abroad. Nowadays, what most home bakers want is a high-quality product (flour) that can fulfill its intended purpose, whether it be for baking pizza or different types of bread.

So, how can this be achieved?

The solution is quite simple – Italy imports wheat with a high(er) protein content from various parts of the world, such as North America, Australia, Russia, Ukraine, Germany, and other European countries. This imported wheat is then mixed with local Italian wheat, resulting in flour with a sufficient protein content that is suitable for a wider range of baking applications; And this is exaclty what the Italians have been doing for over a century, even before 1920.

It is worth noting that Italy consistently ranks among the top ten largest wheat importers globally, and as of the latest report in 2022, it holds the seventh position. Italy primarily imports wheat from Canada, France, the US, Hungary, and Greece.

Surprisingly, Italy does not even make it into the top 20 wheat exporters (currently ranking 25th in 2022). Its main wheat exports are primarily to Tunisia and Algeria, accounting for almost 90% of Italy’s wheat exports. Notably, the majority of this exported wheat is durum wheat, which is preferred for making couscous (Tunisia and Algeria are major consumers of couscous).

While the figures above do not provide a complete picture (a significant portion of Italy’s wheat imports consists of durum wheat, which is used for pasta production), and obtaining specific data is impossible (such as the breakdown between bread and durum wheat imports or the protein content of imported bread wheat), two things are evident:

- Italy heavily depends on wheat imports because its domestic production of bread wheat or durum wheat is insufficient to meet its needs. Furthermore, the bread wheat they cultivate has low protein content and is unsuitable for many modern baking applications.

- Italy’s wheat exports are relatively small and consist almost entirely of durum wheat. This signifies that there is no demand for Italian bread wheat, and understandably so – it is not suitable for many baking applications.

Based on this information, one can conclude that Italian bread wheat is not in high demand, to say the least; But what does this mean in the context of Italian FLOUR?

Italian Flour

Most of us have used Italian flour in some form or another and have likely achieved good results. But how does this align with the information presented in the previous section about the properties of Italian wheat?

The answer is simple: The Italian flours used for making bread and pizza, particularly those that are exported outside of Italy (like Caputo, which is perhaps the most well-known Italian flour worldwide), follow the same process described in the previous section. These flours are a blend of Italian and imported wheat, resulting in flour with the right amount of protein for baking pizzas and bread. Without this practice, Italians would have little to offer in terms of white flour – literally.

In other words, when we purchase Italian flour, we are actually getting flour that contains a varying amount (though usually not insignificant) of non-Italian wheat. To put it simply, the wheat is imported to Italy, milled there, and then exported to the rest of the world as flour.

It is important to note that European flours, including Italian flours, are not required to list dough conditioners/improvers on the package or in the technical data of the flour, such as ascorbic acid, E920, and more. This means that unlike flours in other parts of the world, including the US, which must disclose all ingredients on the packaging – Italian flours may contain various dough conditioners, including vital wheat gluten (to “artificially” strengthen the flour), but we as bakers have no way of knowing the exact composition of Italian flours.

..So now, Italian white flour doesn’t seem as special anymore, does it? 😉

You may be thinking to yourself, “What is this nonsense? I have been using Italian flours for years and they are excellent”.

Yes, it is true that there are many Italian flours that have a high quality and quantity of protein (mainly sourced from foreign wheat). These flours work well for certain applications, such as making Neapolitan pizza. However, they may not work as well for other applications, like making New York style pizza.

When it comes to Italian flour, it is important to understand that there is a significant marketing aspect promoted by Italians themselves. Just because a flour is labeled as “Italian” does not automatically mean that it is superior or suitable for a specific baked good. The level of “suitability” depends on the particular application and desired results, just like any other type of flour. If you are interested in learning more about selecting the ideal pizza flour for your needs, you can read about it in the following article: The Ultimate Guide to Pizza Flour – How to Choose the Ideal Flour for Pizza

Italian Flour and the W Index

For detailed information about the W index and its relevance to choosing pizza flour, please refer to the following article: Flour W Rating Explained (W Index / W Factor).

Here are some key points to understand about the W index in the context of Italian flours:

- When it comes to flours milled from Italian wheat (with low protein content), there is no direct correlation between the protein content of the flour and its “strength”. Two Italian flours can have the same protein content but behave very differently in terms of strength.

- This is different for flours milled from stronger wheat (such as American wheat), where there is an almost direct correlation between protein content and flour strength.

- Since the strength of Italian flours cannot be accurately determined based on protein content alone, the Alveograph test was developed to provide a general indication of their strength, using the W index.

- On the other hand, for flours milled from stronger wheat, their strength can usually be directly determined by protein content, so the W index is not necessary or relevant for these flours.

- The W index is a technical measure designed to evaluate the strength of wheat flours that are relatively weak, mainly used in Italy and France.

- Since the Alveograph test was originally developed to determine the strength of flours milled from weaker wheat varieties, it gives unreliable results for flours milled from stronger wheat varieties.

- That is why the W index can be found on any Italian/French flour, but almost never on non-Italian/French flours (and if it is published for non-Italian/French flours, it’s probably for pizza flours, due to marketing reasons).

Characteristics of Italian Flours

So what ARE the unique characteristics of Italian flours? It can’t all just be marketing, right?!

Enzymatic Activity

Italian flours, especially those used for making pizza, are known for their low enzymatic activity, which is an important characteristic to consider. Unlike some exceptions, like Caputo Nuvola, Italian flours generally do not contain added amylase, resulting in naturally low enzymatic activity.

For more information on how enzymatic activity in flour affects dough and baking, please refer to the section ‘Enzymatic activity in flour and adjustment to baking temperature’ in the article The Ultimate Guide to Pizza Flour – How to Choose the Ideal Flour for Pizza.

In summary, flours with low enzymatic activity tend to slow down browning during baking, making them ideal for high-temperature baking (350C/660F and above), but less suitable for baking in a conventional home oven at lower temperatures; Therefore, Italian flours are particularly well-suited for baking at very high temperatures (for example, for making Neapolitan pizza in a wood-fired oven), but are not ideal for use in a typical home oven.

Dough Behaviour (Extensible Dough)

Beyond the high quality of gluten found in Italian pizza flours, one of the distinctive characteristics of Italian flours is the behavior of the dough they produce. Due to the use of weak Italian wheat as a base, Italian flours produce highly extensible and stretchable dough. This is highly desirable in pizza dough and is something that mills outside of Italy find challenging to naturally ‘replicate’.

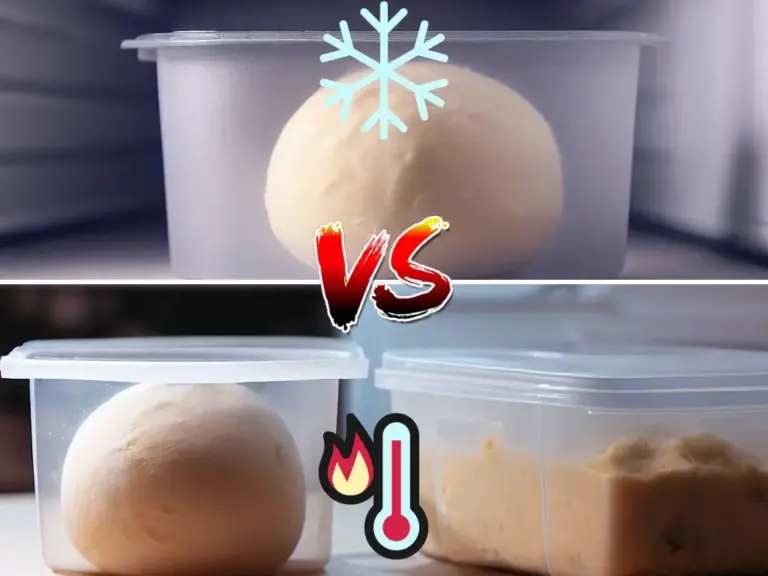

The extensibility of dough made from Italian flour also affects the fermentation process. Italian flour has a greater tendency to flatten during fermentation, whereas dough made from stronger flour will be able to retain its shape better during fermentation due to being more elastic (and generally stronger).

To fully understand the concepts of elasticity and extensibility in dough and their effect on texture, it is highly recommended to read the article on Elasticity and Extensibility in Dough, which provides essential background on these properties.

Gluten Characteristics and Crust Texture Produced From Italian Flour

The unique characteristics of Italian flours, specifically their distinctive gluten properties, are responsible for the distinct open structure and large ‘air bubbles’ in doughs made from these flours. This is because of the characteristics of the Italian wheat, which produces delicate and extensible gluten.

In the picture below, you can see three dry gluten balls that have been baked in the oven. These gluten balls were obtained from a test called the gluten washing test, which is explained in more detail in the article linked above.

The two upper gluten balls are made from local flours, with the right one made from regular all-purpose flour, while the left one is made from bread flour. The bottom gluten ball is made from Caputo Chef flour. What is seen in the picture is the pure form of gluten, without any water or starch from the flour – this is exactly how the gluten appears inside the baked product.

The bottom gluten ball = Caputo Chef

As you can see, there is a significant difference in the gluten structure of the three gluten balls, especially between the gluten from the local flours and the gluten from Caputo Chef’s flour. The gluten from the local flours appears ‘rougher’ and denser in comparison, while the gluten from Caputo Chef’s flour is much more delicate with a more open structure.

It is important to note that the gluten structure and resulting texture obtained from each flour is not necessarily superior or inferior – it depends on the specific application. Certain types of pizzas, such as Neapolitan or al taglio, benefit from the structure and texture provided by Italian flours; On the other hand, this texture may be less desirable for New York style pizza or various cracker style pizzas.

The Granule Size of the Flour

Due to the softer kernel of Italian wheat, Italian flours are typically ground to a finer granule size, which allows them to absorb water faster compared to other flours (smaller granule size = faster water absorption). However, this is undesirable if you plan to use Italian flours as bench flour, as fast water absorption is the opposite of what we want from a bench flour.

You may have even noticed this yourself: when making dough with Italian flour, the water is absorbed relatively quickly compared to other flours (which can also create the false impression that Italian flour can absorb more water).

The granule size does not have any other significant impacts on the dough’s behavior, except during the kneading stage and the speed of water absorption. Nevertheless, it is still worth knowing.

Dough Digestibility

There is a widely held belief that Italian flours are easier to digest, mainly due to their lower gluten content. A lengthy and detailed article will be published in the future to address this topic further; However, for now, it is important to clarify that this is merely a myth, and there is nothing particularly exceptional about Italian flours when it comes to digestion. This claim is simply a marketing tactic employed by Italians to promote their products and food culture.

00 Flour

You can find detailed information about 00 flour in the following article: 00 Flour Explained: What’s So Special About It and Is It Really Necessary for Great Pizza?.

In short, a flour labeled as ’00’ does not provide any useful information about its properties, except for the fact that its ash content does not exceed 0.55% (which is irrelevant for us as bakers). Apart from the ash content, 00 flours can have a wide range of properties, ranging from very strong to very weak, with different gluten properties, etc. Therefore, there is no connection between the actual properties of a flour and its classification as “00”.

In conclusion, it is both possible and recommended to disregard the classification of flour as ’00’, whether for pizza or any other baking purposes. The Italians have successfully promoted ’00 flour’ as a product with special qualities, despite lacking any factual basis; And indeed, it is evident that outside of Italy, the classification of flour as “00” is purely driven by marketing reasons.

Italian Flour – Concluding Remarks

Advantages and Disadvantages of Italian Flour

Advantages of using Italian pizza flours:

- High-Temperature Baking: Ideal for baking at high temperatures.

- Extensible Dough: Produces a more stretchy and manageable dough.

- Quality Gluten: Contains high-quality gluten that is specifically suitable for making pizza.

- Delicate Crumb Structure: Results in an open, airy, and delicate crumb structure.

Disadvantages of using Italian pizza flours:

- Low-Temperature Baking: Less suitable for baking at lower temperatures, such as in a home oven.

- Pizza Variety: Less suitable for non-Italian pizza styles.

- Weaker Flour: Generally weaker compared to other flours.

Obviously, each flour (Italian or non-Italian) should be evaluated individually; The above list is a generalization, but it is applicable in most cases.

Using Italian Flour for Making Pizza: Yay or Nay?

After reading this article, you should now have enough knowledge to decide whether or not to use Italian flour. It’s important to note that the local flours available to you may also be excellent for making pizza, and ultimately – the key to a good pizza lies in using the correct techniques and dough management process, regardless of whether the flour is Italian or not.

The best suggestion in this context is to disregard any marketing hype and try experimenting with different types of flour – you might be pleasantly surprised by the results.

Enjoy the content on PizzaBlab? Help me keep the oven running!

What a fantastic resource PizzaBlab is. You confirmed what I believed about 00 flour and saved a bundle by trying another product (North American) After a 10 hour room temp bulk fermentation then a 14 hours as balls in the fridge they turned out perfect. They rose great in the industrial oven with a top temp 450C and a bottom stone temp of 225C. Thanks again for making such a valuable resource for a new pizzeria owner.

Thank you Leslie, I’m glad you found the content here helpful! Wishing you success with your new pizzeria!

Hi Yuval, i think there is an error on the page. You say 10% protein with 0% moisture will be 11.63% if converted to 14% moisture. However if you add moisture the protein content goes down, not up. You also say 11.63% protein at 14% moisture will be 10% at 0% moisture. This is not possible since removing moisture will drive up protein content. Ascan analogy, if you have meat at 25% protein content and then you dry that meat it will have around 40% protein, since all the water was removed from it.

Awesome content otherwise!

Cheers,

-Ivan

Hi Ivan, thanks for you comment!

I understand where the confusion comes from, but let me clarify how the protein content is calculated:

When we refer to protein content/percentages in flour, it’s important to understand that the ACTUAL amount of protein in the flour remains the same – the difference lies in how it’s presented depending on whether the calculation is based on 0% moisture (dry matter) or 14% moisture.

For example, flour with 10% protein based on 0% moisture would be recalculated as 8.6% protein at 14% moisture. This doesn’t mean we’re adding or changing the absolute amount of protein, just that we’re accounting for the water content in the protein, which adjusts the percentage. The actual amount of protein (obtained using the Kjeldahl method) doesn’t change, just how it’s calculated based on the moisture content.

Unlike in the meat example, we aren’t reducing or “concentrating” the protein when using a different moisture basis for calculation. It’s purely a matter of whether or not water content is included in the calculation. The actual amount of protein and flour remains the same.

The protein content of the same flour will vary depending on the moisture basis used for the calculation, either 0% or 14%. Consequently, European flours will always seem to have a higher protein content since comparing a dry basis calculation to a 14% moisture calculation makes the protein content appear higher.

I hope this helps clear things up 🙂